By Sayyid Husayn Sharafuddin – a professor and faculty member at the Imam Khomeini Educational and Research Institute. He is also a member of the editorial board of the Lifestyle Studies Research Journal.

Translated by Sayyid Ali Imran

Abstract

Celebrity culture stemming from the dominance of modernist discourse, the expansion of mass media, and especially the rise of social media, has become a highly influential cultural force in Iranian society. The central concern of this study is to explore the nature of celebrity culture and the critiques levelled against it from the perspective of Islam, drawing on Qur’anic verses and prophetic traditions. The research methodology involved document-based data collection and an analytical-critical approach to data analysis.

Findings from the study indicate that celebrity culture is not categorically or entirely rejected in Islam. Nevertheless, the contemporary and common forms of celebrity culture are subject to numerous critiques within the Islamic worldview. According to Islamic reasoning, celebrity culture is criticized for issues such as the prioritization of fame and visibility, the superficialization and trivialization of culture, the replacement of true heroes with celebrities, blind imitation, arrogance and rebellion, and the increasing prevalence of performative or ostentatious behaviour.1

Introduction

The phenomenon of “fame” and being well-known has existed throughout history in all societies. Being known to the public and attaining public recognition has manifested in different forms across time. Prior to the modern era, fame was primarily achievement-based and was the dominant and widespread form of public recognition. On this basis, individuals such as warriors and brave heroes, scholars and religious leaders, inventors and philosophers, great politicians, devout worshippers and ascetics, philanthropists, and artists with genuine talent were considered renowned figures among the general populace. The defining characteristic of achievement-based fame was that it rested on significant and deserving accomplishments. From this perspective, society and history have always been a stage for the emergence of heroes and elites whose widespread fame was owed to their major successes, authentic abilities, and their contributions to the welfare of others.

In the modern era, however, influenced by factors such as the growth of instrumental rationality, the expansion of urban life, increasing division of labour, and most significantly the emergence and proliferation of mass media, the social presence of achievement-based fame as the dominant form of recognition gradually declined. In its place, the celebrity emerged as the prevalent and widespread form of recognition in society. Unlike fame, celebrity status is based on frequent media appearances and activities designed to attract attention. The gradual spread of celebrity culture, alongside social and cultural changes such as the diminished role of organized religion in society, urban population growth, increased affluence and leisure time, and the rise of consumer culture, has led to the formation of a full-fledged celebrity culture. Within this culture, celebrities have gained prominent status as role models in society. Following news and content related to celebrities has become important to audiences and many members of the public. Media outlets have also found it valuable to report on celebrity activities and stances, and values, norms, and social rules, such as being seen, becoming famous, and publicly disclosing one’s personal life, have become widespread and institutionalized.

The growing expansion of celebrity culture and its resulting effects—such as the transformation of visibility and fame into public obsessions, the widespread identity formation and imitation of celebrities by fans and audiences, and the increasing social, cultural, and political influence of celebrities on public life—has turned celebrity culture into one of the deepest cultural phenomena in Iranian society. On this basis, celebrity culture influences both individual perception and cognitive frameworks: individuals tend to regard as real or true whatever is expressed by celebrities or is frequently repeated and visible in public discourse. Moreover, celebrity culture plays a profound role in shaping identity, determining how individuals perceive their ideal selves and how they believe they should act or present themselves.

As a result, people come to interpret their ideal self and true success in terms of how effectively they can present a visible and appealing image of themselves. Individuals derive their ideals, aspirations, and models of how to be from celebrities, and they align their own behaviours—including clothing style, speech patterns, ways of interacting with others, and more—with what celebrities promote. Additionally, in celebrity culture, the social and political actions of celebrities influence the social and political engagement of individuals. This can be observed in events such as the 2013 presidential elections, the currency market fluctuations in 2018, and the formation of grassroots campaigns to aid earthquake and flood victims.

Given the dominance of Islamic culture in Iranian society and the necessity of aligning societal goals, ideals, orientations, policies, and actions with the principles that ensure true human happiness and fulfillment—namely, the teachings of Islam—and considering the strong relationship between celebrity culture and issues like identity and modes of social and political action (which are closely tied to human salvation or downfall), a critical question arises: What exactly is celebrity culture, and what critiques does Islam offer of it?

Accordingly, the present study specifically aims to answer the question: What is celebrity culture, and what criticisms can be made of it from an Islamic perspective?

Conceptual Clarification of the Study

1. Fame

The term fame in the scholarly literature on celebrity studies has both a general and a specific meaning. In its general sense, fame refers to widespread recognition among the public. Accordingly, any individual who becomes widely and publicly known falls under this general definition of fame—whether that fame results from a great and worthy accomplishment, from a negative trait or characteristic, or from frequent and repeated media appearances.

In its specific sense, however, fame carries a narrower and more qualified meaning. It refers to a type of broad recognition that arises from significant and admirable achievements (Rowlands, 1995, pp. 49–96). Figures such as Ibn Sina, Haj Qasem Soleimani, and others are prominent examples of fame in this specific sense.

2. Star

The term star is used to refer to individuals who have gained fame through artistic activity or the entertainment industry (Leslie, 2000, p. 10). A star is someone who has excelled in a particular field—such as acting, music, singing, or sports—and whose high levels of skill and talent in that domain have led to widespread recognition and fame.

In celebrity studies, up until the 1970s, there was generally no clear distinction made between star and celebrity. However, beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a distinction between the two terms became prominent in most scholarly works—for instance, in the work of Marshall (Celebrity and Power), Turner and others (Fame Games), and Rojek (Celebrity) (Turner, 2004, p. 1).

Figures such as Ali Parvin, Dariush Arjmand, and Mohammad Esfahani are clear examples of stars.

3. Celebrity

The term celebrity is often understood in contrast to achievement-based fame. However, some scholars prefer to treat these two terms as synonymous. In the literature on fame, sometimes the term celebrity refers to a new form of recognition that is distinct from achievement-based fame, while at other times, it refers simply to a famous individual who embodies this newer form of recognition. In this section, the focus is on celebrity as a new form of being known, which is often referred to as media-based fame. In this context, if a person’s media fame is accompanied by notable achievements — such as certain religious media figures, preachers, or Islamic military commanders — they may be classified as heroes or as possessing traditional fame. Otherwise, they would be considered celebrities.

Many scholars have identified “frequent media presence” or more precisely, “regular appearance in the media” as a core feature of celebrity status (see: Boorstin, 1961; Rojek, 2001; Leslie, 2000; Driessens, 2009; Turner, 2004; Duflém, 2011; Van Krieken, 2013). Media in this context is not limited to mass media alone; it includes anything that provides visibility, such as coffeehouses, public libraries, and cafés. In some analyses, this feature has been conceptualized using terms like “frequent mention,” “constant visibility,” or “high observability.”

Referring to this defining trait of celebrities, some have concluded that celebrity — understood as media-based fame — stands in opposition to achievement-based fame (Cashmore, 2006). However, a closer look at the reasons behind the fame of heroes reveals that their widespread recognition has always depended on means of disseminating their names and accomplishments (Elliott, 2010, pp. 94–96). Therefore, the commonly perceived opposition between fame and celebrity, based on the notion that fame stems solely from achievement while celebrity arises only from media exposure, does not hold up under scrutiny.

It is worth noting that the methods used to present oneself and secure regular media exposure often possess the trait of attention-grabbing (Van Krieken, 2013, p. 54). In reality, these methods require expressive and communicative skills and must be employed in a way that enables them to stand out among the flood of information and content in daily life, effectively drawing others’ attention and fostering a level of trust and persuasion.

The intense competition among celebrities to be seen, coupled with their strong desire for fame, has gradually led some of them to resort to superficial and base methods of gaining attention. The excessive emphasis by certain celebrities — such as Kim Kardashian and participants in the reality show Big Brother — on using shallow and trivial techniques to maintain visibility has given rise to the perception that celebrities fundamentally lack any noteworthy accomplishment beyond their ability to attract public attention (Turner, 2004, p. 9). Hence, it can be concluded that celebrity is a continuum, and in terms of examples, it can range from individuals who have substantial achievements to those whose only notable trait is their ability to capture public attention.

Individuals such as Hassan Reyvandi, Mohammadreza Golzar, Behnoush Bakhtiari, Amirhossein Maqsoudlou (Amir Tataloo), and Donya Jahanbakht are clear examples of celebrities.

Literature Review

Several works are relevant to the present study, including the following:

Hourieh Bozorg (2012), in her doctoral dissertation titled “A Conceptual Configuration of Celebrity Culture in Iran,” investigated the structuring of celebrity culture in Iran with a focus on the Instagram pages of Iranian female celebrities. She approached the research question in three stages. In the first stage, using a descriptive-analytical method, she explored the conceptual formation of celebrity culture in global literature. According to her, “self-branding,” “self-optimization,” and “sexual self-disclosure” are among the key aspects of agency within celebrity culture. In the second stage, celebrity culture was reinterpreted based on Islamic thought. The findings indicated that celebrity culture is fundamentally a culture of “lust for fame,” encompassing four dimensions: the lust for wealth, lust of the stomach, emotional lust, and sexual lust. In the final stage, based on the previous findings, three celebrities — Bahareh Rahnama, Behnoosh Bakhtiari, and Donya Jahanbakht — were selected. Through analyzing their Instagram pages, the researcher extracted the specific rules and strategies of becoming a celebrity in the style of Iranian women and presented them through a thematic network. This research bears a significant resemblance to the present study in that it critically examines celebrity culture and engages with Islamic perspectives. However, like many other works, it presents only a general and limited critical evaluation of celebrity culture without addressing its multiple dimensions in depth.

Hossein Asadi and Ehsan Shahghasemi (2012), in their article “A Pathological Assessment of the Influence of Fame Culture on Youth Fashion from an Islamic Perspective,” examined the negative impacts of fame culture on youth clothing styles from an Islamic viewpoint. Assuming that fame culture has both positive and negative aspects, their study focused on the harms of its negative dimension. Their findings indicate that, from the Islamic perspective, fame culture leads to four key harms in clothing: display-seeking, consumerism, fashionism, and the transformation of social values related to attire. This research shares similarities with the present study in its effort to uncover Islamic perspectives on fame culture. However, since it focuses specifically on clothing and does not discuss broader critiques of celebrity culture, it differs in scope and emphasis.

Elliott (2006), in the article “Plastic Bodies: The Influence of Celebrity Culture on the Rise of Cosmetic Surgery,” critically examined the extent to which celebrity culture has contributed to the increase in cosmetic surgeries. Utilizing Horton and Wohl’s theory of “parasocial interaction” as well as Thompson’s concept of “intimacy at a distance,” the study evaluates how the appearances of celebrities influence identity formation, imitation, and social desires. The results show that popular and media culture today has shifted its focus from the personalities of celebrities to their body parts and artificial enhancements. This work is similar to the present study in its adoption of a critical approach to celebrity culture, but since it does not address Islamic views, it is distinct in its framework.

Hadi (2007), in the article “The Ethical Ruling of ‘Fame-Seeking’ from the Perspective of Islamic Ethics,” reviewed the views of Muslim ethicists regarding the desire for fame. The researcher aimed to determine the ethical rulings on fame-seeking, as well as identify legitimate and illegitimate examples of it.

Mehdi Rahbar (2002), in a study titled “Libās al-Shuhrah (Clothing of Fame),” explored the jurisprudential ruling on wearing garments associated with fame. The conclusion reached in this study was that, according to the widely held opinion of jurists, wearing clothing that is characterized as “clothing of fame” is considered impermissible based on obligatory precaution. Although these two studies examine Islamic perspectives on fame, they do not engage with celebrity culture as a whole and are therefore distinct from the present research.

What distinguishes this study from prior works is that in earlier research, a critical evaluation of celebrity culture from an Islamic perspective was not the primary research question. Each study attempted to address particular aspects of the topic from a specific angle. This research, however, seeks to examine the critical evaluation of celebrity culture from the viewpoint of Islam as its main subject of inquiry. To date, no published work has systematically explored the criticisms directed at celebrity culture from an Islamic perspective.

The Nature of Celebrity Culture

“Celebrity culture” is one of those concepts that, despite its ambiguity, is frequently used in the analyses and explanations of scholars and theorists who work in the field of fame. As an analytical concept, celebrity culture refers to a transformation that is unprecedented and has emerged particularly in the early 21st century. Today, fame has taken on an unprecedented significance in people’s daily lives. Celebrities are present across a wide array of social arenas, and the media — which once viewed the coverage of celebrity lives and gossip as trivial and worthless — now continuously and repetitively reports on the news and controversies surrounding celebrities.

Celebrity culture is ubiquitous and has become an important part of people’s everyday lives. Turner (2004) and Nayar (2013) both affirm this view. Based on such observations, Cashmore asserts that whether we like it or not, celebrity culture is with us. It surrounds us and even attacks us. Celebrity culture shapes our thoughts, our approaches, our styles, and our behaviours. This influence is not limited to die-hard fans of celebrities but includes all members of society (Cashmore, 2006, p. 8).

Sean Redmond describes the essence of celebrity culture in this way: celebrities matter because they play an important role in how we connect and how we come to understand ourselves as beings who interact within the modern world. Celebrity culture encapsulates relationships of power, is tied to identity formation and shared imaginaries, and operates in global commercial circuits where famous individuals are perceived as not being bound to national borders or geographic boundaries (Elliott, 2005, p. 127).

Turner argues that the omnipresence of celebrities in mass media across the modern world compels us to consider it as a new development rather than a continuation of an old condition. The cultural visibility of celebrities has reached unprecedented levels in today’s world, and the role that fame plays in various dimensions of culture has expanded and intensified several times over (Turner, 2014, p. 4).

Although there is no universally accepted definition of celebrity culture, many analysts have pointed to the pervasiveness of celebrities and the spread of their underlying cultural logic as central themes (Rojek, 2014; Turner, 2004; Elliott, 2010). In truth, the concept of celebrity culture refers to a condition in which celebrities are widely present and active in diverse social arenas such as business, education, entertainment, religion, health, politics, and the arts. They shape interpersonal relationships and social dynamics and, most importantly, they play an active role in the production and reproduction of cultural meanings (Driessens, 2009). The cultural logic of celebrity refers to values and norms such as the glorification of fame and visibility, the delivery of attractive and watchable performances, and the constant production of novelty and reinvention. This logic influences and overshadows the process by which celebrities produce and transmit cultural meaning.

Thus, celebrity culture is a concept that highlights the growing expansion and penetration of celebrities and their cultural logic across various domains of collective human life. For this reason, some analysts argue that the word “culture” as used in “celebrity culture” does not correspond to the conventional and standard meaning of culture. Rather, it signals challenges and concerns that go beyond values, beliefs, customs, and lifestyles and speak to the potential transformation of social, political, and economic structures due to their takeover by celebrity influence (Van Krieken, 2003, p. 0).

The Components of Celebrity Culture

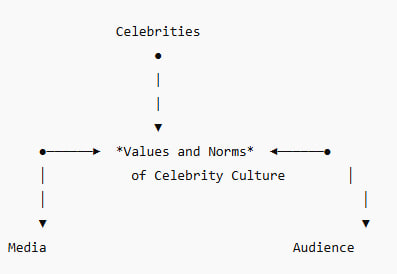

Although at first it may seem that the celebrity is the sole component of celebrity culture, it must be noted that the celebrity is only one part of what constitutes this culture. According to Cashmore, the celebrity is both the least significant and yet the most fascinating element of celebrity culture (Cashmore, 2005, p. 1). Many scholars identify four core components of celebrity culture. However, there is no consensus among them regarding what these four components are. Gamson considers the celebrity, the audience, the media, and the meanings constructed through their interaction as the four principal components of celebrity culture (Ferris, 2011). Others identify celebrities, the media, the audience, and the celebrity production industry — which includes managers, advertisers, and certain media elements — as the main components (Douglas and McDonnell, 2010). Following Cashmore, the four components highlighted here are celebrities, audiences, media, and values and norms (Cashmore, 2005, p. 60). The following section will elaborate on each of these components.

1. Celebrities

Celebrities are regarded as one of the most important elements of celebrity culture. This is largely due to their significant presence and influence in various social arenas, and beyond that, their transformation into role models. From the perspective of Richard Dyer, celebrities today articulate what it means to be human — the particular understanding we have of a person or individual is the same one they express and put on display (Dyer, 1986, p. 7). Many of our behaviours within celebrity culture are shaped by the influence of celebrities. In reality, celebrities, through their choices, present both imagined and real options to the public, and people, through identification, imitation, and selection of these options, shape their identities to resemble them. As Cashmore puts it, we see the clothes celebrities wear, the cars they drive, and the houses they live in, and we want to be like them (Cashmore, 2005, p. 50).

Celebrities strive to be seen more effectively and attract the attention of audiences by employing various strategies and methods. The desire to be seen and become famous, alongside the growing competition among celebrities to be more visible, has gradually led some celebrities — especially internet celebrities — to adopt superficial and lowbrow techniques to capture public attention (Rojek, 2014, p. 10; Cashmore, 2005, p. 60).

2. Audiences

Audiences are another core component of celebrity culture, to the extent that celebrity culture would be inconceivable without them. In fact, a celebrity’s visibility and fame depend on the audience’s recognition (Rojek, 2014, p. 10). It is the audience’s interest in following the work and activities of celebrities, talking about them, and learning about the details of their personal lives that sustains celebrity culture.

In this culture, audiences often shift their attention away from important matters, major accomplishments, or outstanding achievements and instead focus on learning about, searching for, and discussing the minor, peripheral, sensational, or emotionally charged aspects of the lives of their favourite figures.

Although it may initially appear that the celebrity is the only one influencing the audience, research shows that audiences also exert some influence on celebrities. In order to maintain continuous visibility and repeated presence in the media, celebrities are compelled to offer what pleases and appeals to the audience. From this perspective, what is presented by the celebrity is not necessarily their authentic self, but rather what the audience finds interesting and attractive. Hence, the audience does not play a merely passive role; they take on an active and conscious role in shaping celebrity culture (Stever, 2003, p. 65).

Audiences in celebrity culture are not homogeneous in their following and engagement. They range from indifferent individuals who pay little attention to celebrities or their news, to casual followers, fans, and deeply devoted enthusiasts.

3. Media

Media in this context refers to both mass and social media, including images, illustrations, films, magazines, newspapers, radio, television, cinema, the internet, and social media platforms and channels. On one hand, the media has provided an unprecedented platform for celebrities to showcase themselves to the public. On the other, it has enabled the public to search for, snoop into, follow, and gather information about the lives and news of celebrities.

In the landscape of celebrity culture, media outlets have shifted their attention away from reporting fundamental news to covering marginal, sensational, and everyday content. The beginning of this shift can be traced to the work of Walter Winchell, a newspaper columnist. He expanded the coverage of private lives in newspapers. In 1930, at a time when most editors refrained from publishing even basic announcements like an upcoming birth for fear of overstepping boundaries, Winchell launched a revolutionary column in which he reported on topics such as romantic affairs between actors, illnesses of gangsters, impending deaths of public figures, divorces, and numerous other minor and private subjects that were previously hidden from the public eye (Turner, 2014, p. 12).

4. Values and Norms

The desire to “be seen” and the urge to “see” others form a complementary pair that underlies all forms of fame. Being seen has no meaning without an audience that pays attention and talks about the individual, just as seeing and paying attention would be meaningless without figures who display and showcase their accomplishments. All of us have an innate inclination to be noticed, to receive attention, and to be recognized—just as we naturally tend to observe, investigate, and inquire into the lives of others. While the impulse to be seen and to see has deep roots in human social existence, their social manifestation, as well as the degree of importance attached to them, has varied across historical periods.

In the context of celebrity culture, the act of seeing and being seen has undergone two major transformations. First, these acts have been elevated to the level of widespread social values, becoming an unprecedented public preoccupation. Second, the content and object of this attention have shifted—from an interest in learning about, discussing, and investigating significant achievements and meaningful successes, to a focus on the mundane aspects of others’ daily lives, along with trivial and marginal details that lack substantive importance.

A historical survey shows that, until the last century, the general public had limited interest in seeking fame. Fame and the pursuit of it were considered secondary values at best. However, in the current century, being visible, becoming famous, and staying in the spotlight have transformed into superior values among the public. This shift has gone so far that some have remarked, “A life that is not seen is not worth living” (Gamson, 2011, p. 861). Previously, in public discourse, people strove to learn about important matters and notable achievements, paying little attention to the peripheral aspects of prominent individuals’ lives. Today, however, acquiring knowledge of these marginal details has become a popular and enjoyable form of entertainment (Cashmore, 2006, pp. 5–6).

In addition to values such as visibility and receiving attention, as well as seeing and paying attention to others, certain norms, such as the constant novelty of content and the performance of attractive displays, have become entrenched features of celebrity culture.

Based on the above explanation, the relationship between values and norms and the other components of celebrity culture, namely, celebrities, audiences, and media, can be outlined accordingly:

Critical Evaluation of Celebrity Culture from an Islamic Perspective

One of the complexities in critically evaluating celebrity culture as a modern phenomenon is that we are not dealing with a uniform or homogenous phenomenon. Celebrity culture manifests in highly diverse and varied forms, which makes presenting it to Islamic sources for a broad evaluation and adopting a definitive critical stance toward it a complex and ambiguous task. One of the preliminary questions to be posed to Islamic thought is whether the public displays and the essence of celebrity culture are categorically prohibited in Islam, or whether only certain forms of it—which have been shaped by Western cultural and social conditions and have become the dominant forms of this phenomenon—are to be rejected. There is no doubt that a comprehensive examination of primary sources is required to derive a detailed Islamic position on this matter. However, in brief, it can be stated that celebrity culture as a whole, in all its forms and manifestations, is not outrightly prohibited in Islam. Nonetheless, it is equally undeniable that the current dominant expressions of celebrity culture—due to their inclusion of clear deviations—are subject to serious critique from Islamic legal, ethical, and pedagogical perspectives.

The Centralization of Fame and Visibility

One of the prevailing values in celebrity culture is the pursuit of visibility and fame. It is clear that the mere effort to be seen and to become famous, if it serves as a means to attain higher spiritual or social goals, is not only not condemned in Islam but can be justified. What is objectionable and prohibited is when the effort to be seen and to attain fame becomes the ultimate and intrinsic goal of individuals.

Upon consulting religious sources related to the subject of fame, it initially appears that fame or becoming famous is inherently blameworthy and has been strongly prohibited. For example, Imam al-Sadiq (a) says: “Fame—whether good or bad—leads one to the Fire” (al-Kulayni, d. 941 AH, vol. 5, p. 466). In another narration, Imam Ali (a) is reported to have said: “I know of nothing more harmful to a man’s heart than the sound of footsteps behind him” (Warram b. Abi Firas, d. 605 AH, vol. 2, p. 56). The phrase “the sound of footsteps behind him” is a metaphor for someone becoming famous and attracting followers and admirers around them.

However, in contrast to this set of narrations, there are other verses and narrations that praise fame. For instance, the Holy Qur’an in Surah al-Inshirah considers one of the divine blessings granted to the Prophet (p) to be his fame: “And We raised your mention” (Qur’an, 94:4). Allamah Tabataba’i, in his commentary on this verse, writes that the “raising of one’s mention” means one’s renown becomes widespread and elevated above all other names, and that Allah caused the Prophet’s name to be associated with His own name, to the extent that in the Shahadatayn—which forms the foundation of God’s religion—the Prophet’s name is mentioned alongside that of his Lord. Allah made it obligatory upon every Muslim to mention the Prophet’s name with the name of Allah in every obligatory prayer each day (Tafsir al-Mizan, vol. 20, p. 316).

In another narration from the Prophet (p), when a man performs an act sincerely for the sake of the Hereafter and people end up praising him, the Prophet said: “That is the glad tidings being hastened for the believer in this world” (Ibn Babuwayh, d. 381 AH, p. 100). The “glad tidings” in this hadith imply that becoming known and beloved among people can be considered a divine blessing and an opportunity to serve God more.

To reconcile these two seemingly conflicting sets of teachings, one may conclude that fame in itself—as a social position and form of capital—is not inherently prohibited in Islam. Many of God’s prophets, some of the infallible Imams (a), and notable religious scholars have, for the sake of influencing society, guiding the people, and helping them attain salvation, possessed varying degrees of fame (Fayd Kashani, d. 1091 AH, vol. 5, p. 450). Therefore, what is prohibited in Islam is the love of fame or the pursuit of fame for self-serving purposes (al-Naraqi, n.d., vol. 2, pp. 900–901).

One of the most serious challenges of celebrity culture is that visibility and the pursuit of fame have become intrinsic and ultimate goals. This is clearly evident in Western celebrity culture today. When fame becomes the end in itself, the genuine Islamic goal, proximity to God and earning His pleasure, is marginalized. What was once supposed to be a means of reaching Allah becomes the very obstacle and chain that hinders one’s spiritual elevation (Mutahhari, n.d., vol. 24, pp. 661–666).

Superficiality and Vulgarization of Culture

Another challenge and harm posed by celebrity culture, which many analysts have highlighted, is the superficiality and vulgarization of culture. Celebrity culture is fundamentally built on the principle of seeing and being seen, and achieving this visibility is closely tied to engaging in specific activities designed to attract attention. In other words, within this culture, an individual becomes visible and garners attention only when they offer a visible performance and present themselves in a striking way through captivating acts. The constant pursuit of public attention gradually reduces culture and cultural activities to a collection of performative, shallow, and vulgar behaviours. This is often because such figures tend to be uneducated and lack cultural depth, and there is fierce competition among them to capture maximum audience attention and visibility. As a result, resorting to shallow and low-quality methods becomes the easiest and least costly path to win over the masses.

Therefore, mere visibility and being seen are not inherently condemned in Islam, unless such displays become excessive to the point that the entire focus of one’s being is sacrificed for the sake of attracting attention. In other words, flamboyant self-display driven by fleeting desires and lustful motives is what Islam disapproves of, not every form of being seen.

One of the key Qur’anic terms used to deduce Islam’s stance in this regard is tabarruj. The Qur’an states, “And remain in your homes, and do not display yourselves as was the display of the former times of ignorance” (al-Ahzab: 33). According to this verse, the wives of the Prophet (p) were prohibited from tabarruj. Allamah Tabataba’i interprets tabarruj as public self-display, noting that the term “burj” (tower) refers to something prominently visible to all. Mostafavi also traces the root of tabarruj to the notion of appearance and attractiveness, specifically, an appearance that captivates others. Thus, a tall and grand structure is called a burj, and likewise, a woman who beautifies herself and reveals her charms to influence others’ hearts is also referred to as a burj. Based on this understanding, commentators and jurists have concluded that tabarruj is forbidden for women. Therefore, if a woman intentionally reveals her adornments to attract attention, her act is religiously prohibited. It is worth noting that tabarruj has various manifestations—it is not limited to clothing. It can also appear in one’s speech, manner of walking, or gaze. Although the verse explicitly addresses women, other Qur’anic verses—particularly verse 69 of Surah al-Ahzab—make it clear that tabarruj is not exclusive to women; men are also included in this prohibition.

Another key term used to derive the prohibition of excessive attention-seeking is libās al-shuhrah (garment of fame). This refers to clothing that makes a person stand out from others and draws heightened attention. Imam al-Sadiq (a) said, “Indeed, Allah the Blessed and Exalted detests garments of fame.” According to this narration, God dislikes the wearing of clothes that cause an individual to become distinguished and attract attention. Another narration from Imam al-Husayn (a) states, “Whoever wears a garment for fame, Allah will clothe him on the Day of Judgment with a garment of fire.” These narrations indicate that seeking fame through cheap, sensational, lust-driven, and pleasure-seeking means is condemned. Thus, not every method of attracting attention is permissible.

In jurisprudential texts and legal verdicts, wearing libās al-shuhrah is explicitly declared haram. In our era, particularly with the advent of social media and television, the use of vulgar and inappropriate behaviours purely for the sake of attracting others’ attention has become increasingly possible. As a result, celebrity culture has turned into a platform for promoting shallow and vulgar conduct. These include the exhibition of one’s body, or full nudity, the propagation of crude and inaccurate but provocative statements, the display of extravagant and luxurious lifestyles devoid of struggle or meaning, such as showcasing luxury items, various forms of entertainment that are often impermissible, consumption of forbidden foods and drinks, and other similar acts.

The Replacement of Heroes with Celebrities

Celebrity culture has opened an expansive arena for the activity and influence of celebrities. In this culture, celebrities gain greater visibility, attract widespread public attention, exert considerable influence on the behaviour and opinions of large portions of society, and enjoy high levels of respect, popularity, and social status. They have become role models whose actions and lifestyles play an important role in shaping the identities of their audiences.

From an Islamic perspective, one of the critiques levelled against celebrity culture is that the prominence and influence of celebrities in society have grown so much that they have effectively replaced heroes and great figures, pushing them to the margins. There is a concern that societies and cultures that were once spaces for the greatness, activism, and moral influence of heroes in fields such as science, religion, ethics, literature, art, chivalry, military service, and politics are now being surrendered to celebrities—individuals whose main activities revolve around entertainment, emotional expression, imagination, and attraction.

While Islam is not entirely opposed to the entertaining or emotional aspects of human expression seen in celebrity behaviour, its spiritual and moral orientation emphasizes the pursuit of higher goals: salvation in the Hereafter, which naturally stems from a life of faith in this world. Since achievement-based fame aligns more meaningfully with Islamic moral and educational aims, Islam gives special importance to the kind of fame rooted in noble accomplishments and meaningful contributions. According to Islamic logic, a clear distinction must always be maintained between heroes and celebrities, and precedence should be given to heroic personalities while recognizing their proper ranks.

Given that the actions and behaviour of famous figures influence and are imitated by many, their role as models becomes increasingly prominent, shaping social identity in profound ways. Therefore, from an Islamic standpoint, those occupying such positions should be individuals of virtuous character, significant achievement, and worthy of imitation and emulation. The Qur’an identifies the Prophet Muhammad (p) and Prophet Abraham (a) as the finest examples for humanity (al-Ahzab: 21; al-Mumtahina: 4). Throughout history, prophets, infallible Imams, distinguished scholars, and upright individuals have sought social recognition not for vanity but to fulfill their duty of guiding people toward truth and righteousness (Fayd Kashani, 1091 AH, vol. 5, p. 450). In contrast, what has become problematic in modern celebrity culture is the replacement of true heroes with superficial celebrities.

Blind Imitation

Blind imitation is another major issue within celebrity culture, especially concerning its followers and audience. Admirers of celebrities often, whether consciously or subconsciously, imitate them in behaviour, speech, or appearance. Imitation or influence, in itself, is not condemned in Islam—it may even be positive if the imitation leads to rational, beneficial, or moral outcomes. Indeed, the close relationship between celebrities and their audiences can serve as a channel for learning and the transmission of beliefs, values, attitudes, manners, and behaviours. When these elements possess positive moral value, imitation can be seen as praiseworthy.

However, from an Islamic perspective, what is objectionable is when such imitation occurs blindly and passively, without reason or discernment, or when the content being imitated is corrupt, deviant, or harmful. Unfortunately, admirers sometimes become so enamoured with celebrities that they view even their inappropriate, unethical, or immoral actions as acceptable or admirable.

The Qur’an strongly condemns blind imitation without knowledge or reflection. For example, in Surah al-Shu‘ara (verses 69–103), following ancestral traditions blindly is described as a major reason for rejecting the messages of prophets and turning away from truth. Similarly, in Surah al-A‘raf (verse 28), the Qur’an criticizes the polytheists who justified their immoral practices by claiming to follow the customs of their ancestors. Such behaviour, devoid of reflection or understanding, is condemned repeatedly in Revelation.

Imam Ali (a) also stated: “There is no obedience to anyone in disobedience to Allah; true obedience is only in what is good.” This narration makes it clear that imitation in sinful or unethical acts is never permissible, whereas imitation in virtuous and praiseworthy acts is legitimate and commendable.

Blind imitation is often driven by immaturity of thought, personality worship, traditionalism, excessive affection, prejudice toward one’s group, or tribal loyalty. In the context of celebrity culture, the main motivations for blind imitation include intellectual immaturity, idolization of personalities, and the desire to belong to a social group. Such imitation may manifest in copying a celebrity’s style of dress, hairstyle, manner of speech, or behaviour—often with the aim of gaining fame, popularity, or social status.

This phenomenon is particularly widespread among devoted fans, sometimes described as “celebrity worshippers,” who replicate their idols’ actions in extreme and uncritical ways. Clearly, such imitation is not endorsed by Islam and is, in fact, explicitly prohibited.

Rebellion and Arrogance

One of the harms of celebrity culture is the tendency for celebrities and public figures to fall into rebellion and arrogance. The widespread presence of celebrity culture in society creates exceptional conditions and opportunities for celebrities to exert influence. In such a context, celebrities are often able to engage in private dialogue with high-ranking political officials, comment on both specialized and non-specialized issues, and disseminate superficial, false, or unverified information through the media. Backed by their passionate fans and massive audiences, they can make demands at national or even international levels, hold lengthy emotional conversations with their enthusiastic supporters, enter public or private spaces with overwhelming reception, quickly fulfill their requests within administrative systems, and are frequently described in quasi-divine terms by their admirers.

This extraordinary status often leads celebrities toward pride, self-centeredness, egotism, and insubordination. One of the reasons Islamic traditions warn against the pursuit of fame is precisely due to the risk of such individuals falling into rebellious behaviour. Imam Ali (a) is reported to have said, “I do not see anything more harmful to the hearts of men than the sound of sandals behind their backs [i.e., people following them excessively].” (Warām ibn Abi Firās, 401 AH, vol. 2, p. 65). According to this narration, the gathering of fans around famous individuals, their accompaniment, requests for photos or autographs, and at times, acts of exaggerated admiration and even idolization, play a significant role in leading these figures astray and into arrogance.

Furthermore, in verses 6–7 of Surah al-‘Alaq, the Qur’an identifies a sense of self-sufficiency and detachment from need as one of the core reasons behind human rebellion. Essentially, when a person feels independent of God and attributes their privileged position—truly a divine blessing—to themselves, that itself constitutes a form of rebellion. This problem is especially observable in Western culture, where God and religion have been marginalized and the human self has become central. In other words, in a cultural context that lacks strong ethical virtues and moral accountability, internal checks against celebrity misconduct are either non-existent or function weakly. The sense of god-like status fostered especially by their followers leads celebrities to ignore the necessity of observing moral boundaries. Only the existence of some civil laws and widely accepted social norms serves to contain their actions to some degree.

Therefore, in the Western model of celebrity culture, the emergence of such problems is unsurprising. Islamic teachings strongly caution individuals against placing themselves in positions highly prone to deviation, and if one does find themselves in such circumstances, they are advised to remain alert, mindful, reflective, and engaged in constant self-assessment and spiritual recourse.

The Rise of Performative Actions

Performative action is a type of social behaviour that is carried out with the awareness of others and implies an outward stance that does not match the individual’s true inner beliefs. Detecting this dissonance is often complex and difficult. In such actions, an individual—driven by the desire to influence others—projects meanings through speech or behaviour that differ from their inner thoughts (Anvari, 1393/2014, pp. 55–56). Two main elements define performative behaviour: first, a mismatch between outward action and inward intention; and second, the desire to attract attention and approval from others.

Attracting attention and catering to the tastes of others is a key objective within celebrity culture. Celebrities constantly strive to frame their actions in ways that appeal to fans and audiences. Conversely, audiences tend to pay attention to individuals whose activities they find interesting or noteworthy. As this reciprocal dynamic grows in prevalence, performative behaviour becomes more widespread. Celebrities, influenced by the dominant values and norms of celebrity culture, often try to display conduct that pleases others, even if it contradicts their true intentions and motives.

Such behaviours typically manifest in the form of exaggerated verbal or written expressions of affection, superficial displays of sympathy, staged acts of charity or humanitarianism, excessive respect for the demands of audiences, the artificial inflation of follower counts and likes, and other forms of inauthentic expression.

One of the key Islamic concepts that helps us critique performative behaviour is riyā’ (showing off). In the Islamic ethical system, riyā’ is condemned and considered among the most serious spiritual vices, with scholarly consensus on its impermissibility (Naraqi, n.d., p. 509). Numerous Qur’anic verses and Prophetic narrations prohibit riyā’. For example, the Qur’an states, “They show off to people, but they remember God only a little.” (al-Nisā’: 142).

In a well-known narration, the Prophet Muhammad (p) said: “What I fear most for you is minor shirk (polytheism).” They asked, “O Messenger of Allah, what is minor shirk?” He replied, “It is riyā’. On the Day of Judgment, Allah will say to those who performed deeds for show: ‘Go to those for whom you used to perform and see if you find your reward with them.’” (Warām ibn Abi Firās, 1414 AH, vol. 1, p. 187)

In another narration, the Prophet (p) said: “Allah does not accept a deed in which even a mustard seed’s weight of riyā’ is found.” (Warām ibn Abi Firās, 401 AH, vol. 2, p. 110)

These teachings serve as a strong reminder against falling into the trap of public performance for social approval, particularly when such behavior is disconnected from genuine ethical or spiritual motivation.

Conclusion

Celebrity culture, as a modern phenomenon, encompasses both positive and negative dimensions. Nevertheless, the negative aspects of this phenomenon—rooted in Western culture and social structures—have manifested more widely and profoundly than its positive ones. Although celebrity culture, as a form of popular culture with broad public appeal, holds potential for achieving certain cultural, ethical, and educational goals aligned with Islam, it cannot be regarded as a culture fully compatible with Islamic educational objectives due to its numerous negative traits and manifestations.

Celebrity culture, particularly in its contemporary forms, is subject to multiple criticisms from the perspective of Islam, including:

-

Turning fame into the ultimate goal: This entails the dominance of public approval and popular desire over divine satisfaction, ultimately distancing individuals from closeness to God.

-

The superficialization of culture: The shallow and trivial cultural logic of celebrity culture extends beyond the domain of fame and infiltrates other areas of cultural life.

-

Replacing heroes with celebrities: Celebrities, who promote superficial and crowd-pleasing behaviours, become uncontested social role models and sources of reference, whereas from an Islamic viewpoint, those with noble and elevated achievements are deserving of such positions.

-

Blind imitation: Due to the mass-oriented nature of celebrity culture, it leads audiences toward uncritical, passive imitation and influence, which Islam firmly opposes.

-

Rebellion and arrogance: The vast opportunities and privileges provided to celebrities enable the emergence of egotism, vanity, and rebellious behaviour.

-

Increasing performative behaviours: The prioritization of popularity and the desire to gain others’ approval has become a defining feature of celebrity culture, fostering inauthentic behaviours aimed at attracting attention and trust.

Given the foundations and principles of Islam, whose ultimate goal is to ensure true human felicity through a life of faith, it appears that Islam favours a culture of fame that is distinct from celebrity culture. Such a preferred model would involve benefiting from fame without turning it into an end goal; prioritizing fame based on merit and achievement; emphasizing intellectual and reasoned appeal over emotional and superficial charm in acquiring recognition; upholding the status of true heroes as societal role models; discouraging the pursuit of fame for all; and instituting internal and external mechanisms for monitoring and controlling the conduct of public figures.

From this perspective, the findings of this research can help lay the cognitive and epistemic groundwork necessary for crafting appropriate cultural policies that facilitate a shift from celebrity culture toward a more principled culture of fame.

Sayyid Ali studied in the seminary of Qom from 2012 to 2021, while also concurrently obtaining a M.A in Islamic Studies from the Islamic College of London in 2018. In the seminary he engaged in the study of legal theory, jurisprudence and philosophy, eventually attending the advanced kharij of Usul and Fiqh in 2018. He is currently completing his Masters of Education at the University of Toronto and is the head of a private faith-based school in Toronto, as well as an instructor at the Mizan Institute and Mufid Seminary.